Early Works: "Little Black Bullets" and "Night Notes"

Here are two more old short stories of mine published years ago in a little literary magazine called Expression, during my youthful "literary period," pre-pulp, though there are small hints of the excess exploitation to come. The pop cultural references are still numerous, though my stuff back then was obsessively preoccupied with star-crossed romantic relationships, since I was such a lonely dude, working various odd jobs to survive, getting involved in a series of doomed affairs, and always writing, writing, writing...

LITTLE

BLACK BULLETS

by Will

Viharo

Originally

published in Expression, Winter 1990

He used

his typewriter like it was a machine gun.

Whapwhapwhapwhapwhap.

Rapid-fire rhetoric, words like little black bullets, straight to her

heart.

“I

miss you, I need you, I love you...” he shot.

The

phone rang, and he ceased fire. He let his machine intercept the

message before he self-destructed.

Beep.

Dial tone. Silence.

Maybe it

was her after all, but she was too scared or brave or smart of stupid

to leave a message. She knew he screened all his calls, especially at

night, when he worked on his plays. She knew he was probably

prostrate with grief on the floor, an empty bottle of gin by his

bleeding side, arms outstretched like Jesus. And she still

didn't leave a message, if that had been her and not another

wrong number.

“Fuck

you, fuck you, fuck you,” he typed.

“I

want freedom,” she'd told him three weeks before.

“I

want bondage,” he'd replied.

“I

want to travel,” she said, “alone.”

“I

want to stay home,” he said, “with you.”

“I

want out.”

“I

want in.”

“I

want me.”

“I

want you. Finally we agree on something.”

“We

can't share me anymore,” she said coldly.

“Why

not?”

“I

don't know.”

“I

don't either. Another point in common.”

“I

still love you.”

“I

still love you too. We're on a roll.”

“As a

good friend.”

“Not

as a lover?” he said, internally collapsing.

“...not

anymore,” she forced herself to admit.

“That's

sad.”

“It

is.”

He

sighed, trying not to cry in front of her, even though she

was, at least a little. “I liked it much better when we were

disagreeing,” he said. “We had more to talk about, which meant

more time together.”

“Don't

prolong the agony,” she said, wiping her eyes. “Just let me go.”

“It's

easy for you, isn't it? To just walk away.”

“Yes

and no.”

“This

is no time for multiple choice. You kill me, you know that?”

“Bang,

bang.” Her sense of irony seemed cruel at the time. Maybe it was

her way of dealing with the tension, by plugging holes in it.

His

apartment was like something out of Edward Hopper; stark but

colorful, old-fashioned and dimly lit. And lonesome as hell.

New Age

music played on a CD. It soothed him, helped him relax. He tried to

sleep, but he had to get up soon anyway and start his new job,

delivering newspapers to stands all around town. He hated getting up

early, but it beat office work. It was in an office where he'd met

her. He was an errand boy and she was doing temp secretary work. They

had a brief fling after a few drinks-after-work dates, a Roman Candle

affair; then he got serious, and she got lost.

She was a

sculptress, molding images that pleased her, and hopefully pleased

others enough to pay her rent. She felt restless, and couldn't sleep.

She thought about dialing his number again, hoping he'd pick up

instead of letting the machine do it, because by the time his message

played – a sad blues song about waiting for his baby to call him or

something – she always lost her nerve to talk. She didn't know what

to say to him that didn't sound empty and patronizing and pedantic.

Feelings change, people change, I never wanted a serious commitment,

you know my history, we're still young, you still have your work, how

about those Oakland A's? Forget it. It was like beating a dead

hearse, she thought, I mean horse. Whatever.

She

flipped on the TV to some old movie with Rita Hayworth called Gilda.

In typical film noir tradition, Rita was a femme fatale

breaking the hearts of desperate, shady men on the fringe of society.

Glenn Ford played her ex-lover, now working for her current husband,

some German guy who ran a night club in South America somewhere.

Argentina. Anyway, Rita and Glenn torment the hell out of each other

for the whole show.

She

almost changed channels, but wanted to see how it ended.

He

decided to tune in an old Miami Vice episode on cable. Sonny

Crocket was falling for a French woman who was really setting him up

to get killed and ripped-off by her dealer-lover, played by Ted

Nugent. A song called “Cry” played over the violence and

deception as Nugent and Crockett shot it out; then Crockett arrested

the girl on Miami Beach, cooly putting his shades on to hide his

tears as she walked away with her arm around the waist of another

cop.

He

finished off his beer and flung the bottle against the wall. It

shattered into a million pieces and shards of glass flew everywhere.

He put his hand over his face to protect his eyes from the little

fragments.

Her

loneliness felt like emotional AIDS, and she knew it was terminal,

with no known cure on the market, and she'd tried everything. Gilda

ended happily, with the German husband getting bumped off and Glenn

and Rita going back to New York a happy couple. Only in the goddamn

movies, she thought.

There

was a knock at the door.

“I was

in the neighborhood,” he said meekly as she let him in. “You

know, to start my paper route.”

“I

wish you hadn't have come,” she lied.

“I

need to talk to you,” he said. “I don't understand why we both

need to be unhappy alone. We could at least be unhappy together.”

“That

doesn't make any sense,” she said, pouring them both a drink.

“There's nothing left to say or do. It's just over. No special

reason. Things change.”

“I

miss you,” he whispered. “I need you, I love you...”

“Don't,”

she said, moving away from him, opening her door again. “You should

go. People want their papers.”

“So? I

want you but can't have that. People don't always get what they want,

do they?”

“Please

leave.”

“Did

you try calling me earlier?”

“No.”

“Are

you lying to me?”

“No.”

His eyes

wandered over to the figure she was sculpting, nude, twisted, in

pain. “Nice work,” he said.

“Thanks.

It isn't finished yet.”

“Missing

a penis?”

She gave

him a cold, hard look. “Breasts.”

“Oh.”

“You

should go.”

“I'll

die if I never see you again.”

“Everybody

dies,” she said as he walked out the door.

After

he'd left, she noticed there was blood on the carpet, and wondered

where it came from. She tried to clean it up, but it had stained

already. She covered it up with a throw rug, pretending it wasn't

there, hoping no one would find it and ask her incriminating

questions she couldn't answer. (End)

I wrote Night Notes while I was actually working as a desk clerk at The French Hotel in Berkeley, CA, circa 1989-1991. This fluffy little piece of prose poetry doesn't begin to reflect the truly epic oddness of that place, which seemed to attract all kinds of colorful kooks from around the globe. Later it was expanded into my unpublished novella Shadow Music, which was adapted for this Berkeley radio play in 1996. The themes are nearly identical in both pieces. Years later, inspired by similar experiences, I wrote and published my extremely graphic horror-noir-bizarro novella Freaks That Carry Your Luggage Up to the Room, which went a lot further in capturing the strangeness of that little hotel, albeit in a greatly exaggerated fashion.

NIGHT

NOTES

by Will

Viharo

Originally

published in Expression, Fall 1990

She took

a room in The French Hotel because she wanted to pretend she was

still in the south of France, happy and tan, and not back in

Berkeley, broke and blue. The hotel was in a three-story red-brick

building along with The French Cafe, with neon signs designating

each. She liked the modern, brightly-lit décor of the rooms and the

European fragrances of espresso and croissants. The overall ambience

was casual, almost informal, but clean and well-kept. She pretended

she was residing in a small French villa. In fact, she rarely

ventured outdoors. It was early winter and raining frequently now,

but that was not the reason for her self-imposed isolation. She was

trying to concoct a cocoon, spending mornings and afternoons reading

long, romantic novels in the cafe, and wasting away the evenings

dozing and idly watching television. She hoped this would continue

forever, but the sad fact was she was nearly out of money. It was

almost time to face the real world again, and she dreaded it. Still,

she tried to appreciate the time, and funds, she had left. After all,

life itself is impermanent, she reasoned, so why worry about the

future?

She

fancied herself a poetess, but other than her graduate theses on the

Romantics, in which she provided some updated examples of the mode

from her own talented but dormant imagination, she had nothing to

show for it. She realized that making a living as a poet – even a

successful one – was not a realistic prospect in this day and age,

in this country. One reason for her flight to France had been a vague

desire to become an expatriate, hoping the spirit of Anais Nin would

take possession of her heart and pen. But all she really did was

transfer her dreaming from one continent to another for a few months,

until her savings ran out. Now it was back to Eugene, Oregon, to wait

tables and live in a rustic artists' commune and eventually commit

herself (either way). Her only reasonable alternative – a

nine-to-five job was not in the running – was to simply stay in

this hotel and find a way to freeze time as well as her assets.

At least

she had a sympathetic friend in the night clerk. He fancied himself a

saxophone player, although he didn't know how to play and was too

cheap, and broke (at five bucks an hour) to take lessons. But he

listened a lot to Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday records, hoping

their well-honed blues would, via osmosis, be assimilated by his

heart and soul and maybe even lungs and lips. In the meantime, he had

his job, his room, his cat, his bills, his dreams, and his records.

He hit

it off right away with the poetess who never wrote poetry, since he

was a saxophone player who never played sax. Secretly, he was in love

with her.

“It's

the thought that counts,” he told her one night as they sat

listening to his blues tapes. She smoked and he drank coffee; she had

in her lap an empty notebook and a pencil. She laughed at his

statement, but inside she felt sad and lost. She had to find a way to

justify her existence and pay her hotel tab at the same time, but

soon. This was her last paid night in The French Hotel.

“Tell

the owner I'm thinking about paying my bill,” she told the

desk clerk/sax player.

“I'm

afraid he won't even offer credit for your thoughts,” the desk

clerk laughed.

“Not

even a penny?” she smiled. He noticed her legs as she crossed them.

She let him notice, and didn't pull the hem over her knee.

“Not

that they're not worth anything,” the desk clerk said more

seriously. “Maybe if you wrote them down people would pay to read

them. In a book of poems, I mean.”

“Nobody

cares enough about poetry to support me.”

“That's

probably because you're still alive. People go for dead poets.” He

was trying to balance the books and listen to the music at the same

time. Invariably he screwed up the accounts. He was on notice already

as it was. He was looking for another job, but couldn't find anything

he wanted to do as much as play the sax in a smoky nightclub. Not

even close. He had the soul but not the instrument, the vision but

not the voice. Inwardly, the music never stopped. The trouble with

that was only he could hear and appreciate his compositions and

classic covers. If only he could live inside of himself all the time,

and never come out. He'd invite the poetess in once in a while, of

course. If she wanted to come, that is. He had a feeling she'd like

it in there, given the chance. It was dark and cozy and he wouldn't

charge rent and make her get a demoralizing job.

“My

poems are too sentimental, anyway,” she said, taking a slow, sexy

drag. “Or they would be, if I wrote them down.”

“Today

it's sentimental. Tomorrow, it'll be poignant. That's usually

how it works,” the world-wise desk clerk explained.

“I

see,” she smiled. “So maybe I should just die. As a career move,

I mean.”

“Don't

kid around about stuff like that,” the desk clerk said. “This

time of night, anyway. Gives me the creeps. They don't call it

graveyard shift for nothin'.”

“Sorry.”

She decided to change the subject to something livelier. “I like

your taste in music.”

“Thanks.

So do I.”

“Although

I prefer Patsy Cline myself.”

“I

like her, too. Bluesy voice.”

“Patsy

Cline, Billie Holiday...ever read Sylvia Plath?”

“Nope.

Why?”

“It

seems you have a thing for tragic women.”

“Maybe.

Maybe I do. At least from a distance.”

She took

a long, pensive drag on her cig. “That's too bad. You should take a

closer look sometime.” She met his eyes and they both smiled. He

looked back down at the books. He'd just messed up again. What

the hell – it was fate. Obviously he was meant to be a

fuck-up, or a “social pariah,” in romantic terms. If he didn't

move quickly, his future would catch up with him.

“Have

you ever noticed,” the poetess said abruptly, “that a saxophone

sounds like an orgasm feels?”

He broke

the point on his pencil. “Ummm...I never really put the two

together, to be honest.”

“Think

about it. Hard.”

“You

ever look into a mirror and watch yourself disappear?”

“Do

you want to come to my room?”

“You

didn't answer my question.”

“You

didn't answer mine.”

“Yes,

I would,” he said.

“No, I

haven't,” she said.

“I've

already seen your room,” he said as they walked down the long, dark

hall.

“Not

with me in it,” she said.

“In my

imagination,” he said low, but she heard it.

“Reality's

better,” she said. “Time to trade up.”

She

smiled slyly as she led him to her room. He brought his tape player

and the screwed-up books with him, his blood pounding with

anticipation. At least one fantasy would come true tonight, he

thought, and maybe it would inspire the rest to follow suit.

“Don't

bother,” he said, pulling out the key to her room just before she

opened it herself. He let them in and locked the door behind them.

“What

if the phone rings, though?” he asked, sitting tentatively on the

edge of the bed. “Up at the front desk, I mean?”

“At

2:30 in the morning?” she said, pointing at the digital clock.

She'd left her underthings strewn across the bed. He pretended not to

notice. She went into the bathroom and turned on the shower. “I'll

be out in a minute. I'm just going to freshen up,” she called to

him. He had the accounts open on his lap, and he gazed at them as if

they interested him a great deal. He was slowly deciding to quit

before they fired him, to save time as well as humiliation.

She

appeared in a flimsy fuchsia bathrobe five minutes later. She had her

hair wrapped in a towel. She massaged her scalp and dried her hair as

she turned on the television.

“Why

don't you have cable?” she asked absently as she finished drying

her hair. Her bathrobe fell open and exposed her cleavage, but the

desk clerk nervously kept his nose in his books. Was this a come-on

or a put-on? For once he was more preoccupied with the present than

the future.

“The

owner's too cheap,” he mumbled. He turned on the tape player low,

so that the volume didn't completely drown out the television.

She

flipped the channels quickly, then shut it off. “Nothin's on

anyway,” she said with a grimace.

“You

shouldn't be wasting your time watching television anyway,” the

desk clerk said.

“What

should I be doing, then?” she asked ingenuously as she sat down

beside him on the bed, the warmth of her thigh seeping through his

slacks. She took the account book away from him and tossed it into

the wastebasket.

“Why

did you do that?” he asked, as she leaned even closer to him, so

that her breath touched his cheek.

“I've

had many lovers,” she said, leaning over him and shutting off his

tape recorder. He moved to turn it back on, but she gently

intercepted him, holding his hand in hers.

“If

you've had many lovers,” he said hoarsely, “does that make me

just another statistic?”

“I can

hear you, you know,” she said.

“Hear

what?” he asked, uneasy.

She

began kissing his neck and unbuttoning his shirt. He didn't stop her.

“Your

music.”

“You

just turned it off.”

“I

don't mean that music. I mean the music that has led me from one

bedroom to the next, looking for its source. Sometimes I'd hear it

while sitting in a bar, and a man would approach me, light my

cigarette, and take me home. But I'd wake up feeling empty, hearing

nothing. Then, later, when I was alone, I'd hear it again. I'd try to

write lyrics for it in my notebook, to try to understand it. At first

I thought I was only hearing the music from your machine when I came

here, but now I realize...”

He

cupped her face in his palms and kissed her, long and deeply. He

looked into her dark eyes and was drawn into her little dome-covered

world.

“I've

imagined this moment since the first time I saw you,” he said,

opening her bathrobe fully and kissing her breasts. She moaned and

shut her eyes, and he leaned back onto the bed. “I'm so happy I

wasn't hallucinating.”

“The

music is so loud now,” she whispered. “I can't hear anything

else.”

Later,

after he lay exhausted in her arms, she hummed the music that had

once been trapped inside his head.

“The

night is full of epiphanies,” she said softly.

The next

morning the manager of The French Hotel came in to find no clerk on

duty. She called his home number but it was disconnected. He never

returned for his paycheck.

A week

passed, and the manager finally noticed that room 302 was not

up-to-date on the bill. She marched up to the room and rapped on the

door. When no one answered, she tried all the keys, called a

locksmith, and then the owner, but no one could open the door to 302.

Inside,

the desk clerk sat on the edge of the bed, shirtless, playing his

saxophone as moonlight streamed through the blinds, and the girl lay

beside him with her feet up, writing in her notebook. The digital

clock was stuck at 2:30 a.m., but it was no longer the musician's

responsibility to fix it. They did, however, have cable T.V. The

night would never end.

The police broke into the room and the manager identified the bodies, already cold. The cause of death is still unknown. Late at night, some visitors to The French Hotel claim to hear music, but no one can ever find its source. The lyrics are haunting, people say.

MORE SHORT FICTION by Will Viharo

A WRONG TURN AT ALBUQUERQUE (1982) and THE IN-BETWEENERS (1987)

COFFEE SHOP GODDESS (1990) and THE EMANCIPATION OF ANNE FRANK (1991)

A WRONG TURN AT ALBUQUERQUE (1982) and THE IN-BETWEENERS (1987)

COFFEE SHOP GODDESS (1990) and THE EMANCIPATION OF ANNE FRANK (1991)

PEOPLE BUG ME (2013)

SUCKER PUNCH OF THE GODS (Flash Fiction Offensive) (2014)

THE STICK-UP ARTIST (Flash Fiction Offensive) (2015)

THE STICK-UP ARTIST (Flash Fiction Offensive) (2015)

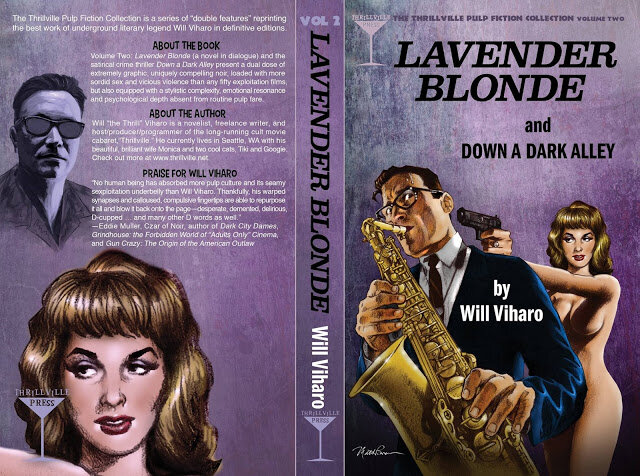

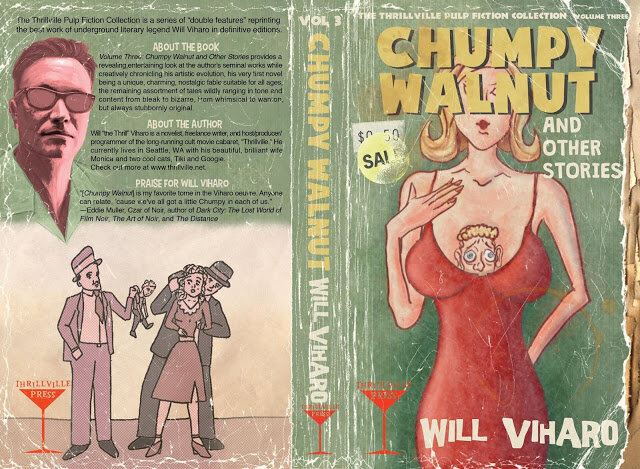

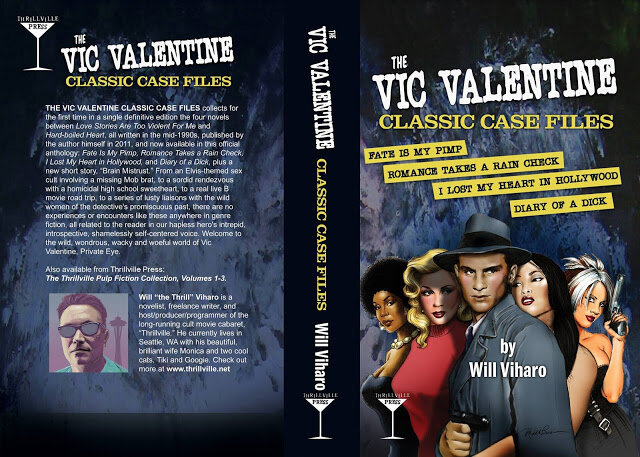

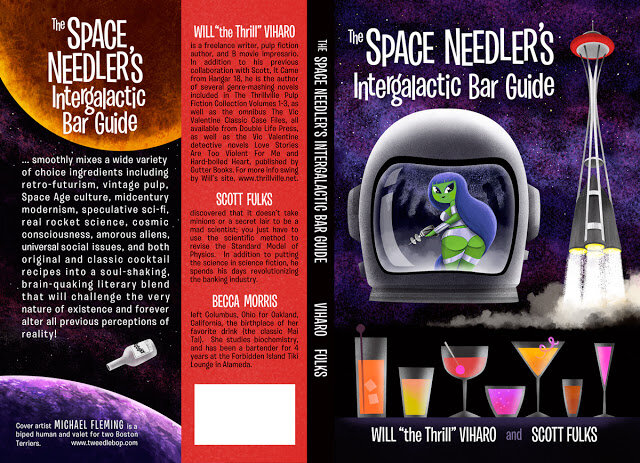

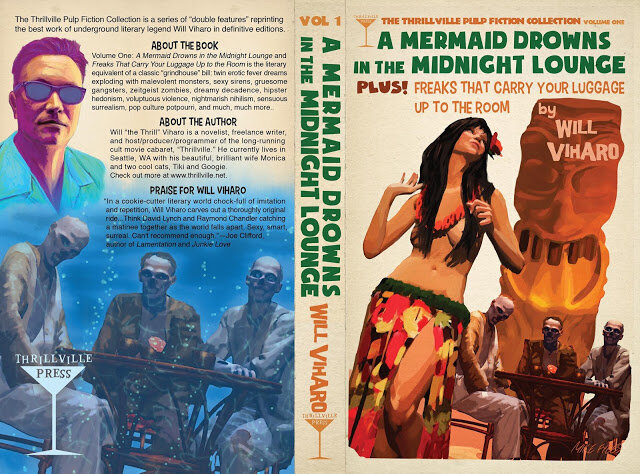

NOW AVAILABLE from THRILLVILLE PRESS:

THE THRILLVILLE PULP FICTION COLLECTION!

| ||||||

| VOLUME ONE: A Mermaid Drowns in the Midnight Lounge and Freaks That Carry Your Luggage Up to the Room BUY

|

| ||||

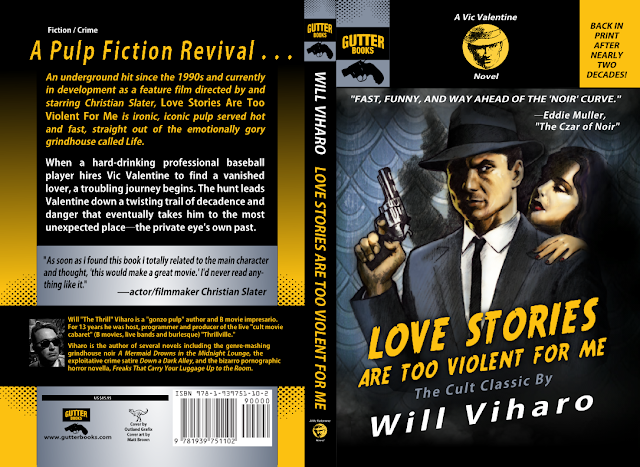

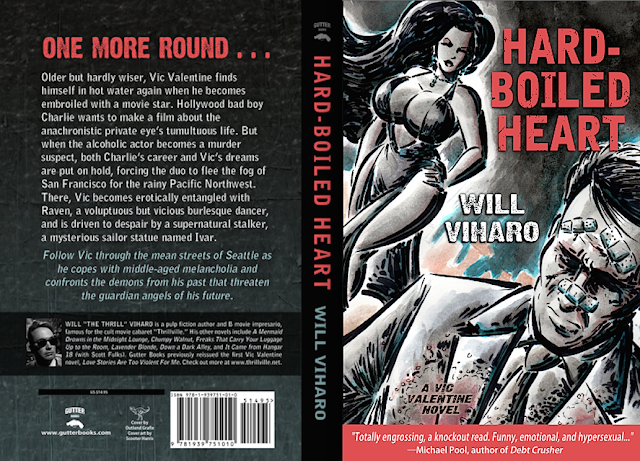

The new Vic Valentine novel HARD-BOILED HEART now available from Gutter Books! BUY

|

My short story ESCAPE FROM THRILLVILLE as well as my Tribute To Ingrid Bergman included in this issue of Literary Orphans

|

My short story BEHIND THE BAR is included in this anthology:

|

My Vic Valentine vignette BRAIN MISTRUST is included in this anthology: |

|

| Screening of the Director's Cut of Jeff M. Giordano's documentary The Thrill Is Gone, Monday, November 17, 2014, 5:30pm at the Alameda Free Library |