Early Works: "Coffee Shop Goddess" and "The Emancipation of Anne Frank"

Presented for your approval - or disapproval, doesn't matter to me now - are two vintage short stories of mine originally published in a short-lived, long-defunct Bay Area literary tabloid called The Rooster and The Raven. Both pieces reveal a very young, ambitious, sensitive, and romantic dreamer at work. Obviously the early influence of J.D. Salinger is apparent, but I think even by then (circa age 27) I had developed my own unique voice, focusing on my recurring themes of loneliness and romantic obsession. Coffee Shop Goddess is my ode to the '80s, set in L.A. and San Francisco, where I spent that decade, peppered with a lot of recognizable pop cultural references, so it's an effective time capsule, both personally and generally speaking. The Emancipation of Anne Frank is inspired largely by my own childhood, though I only spent a brief time of it in New York City, the setting of this story. As you can see, I've changed a lot since I wrote these stories. I've lost my innocence. I'm not sure that's a good thing, as a person, or as an artist. In any case, I'm happy to share them again after all these years, since they preserve a precious part of me that I'll never recover.

COFFEE

SHOP GODDESS

by Will

Viharo

Originally

published in The Rooster and The Raven, 1990

|

| Original illustration |

I called

her Lightbulbs, since she always having bright ideas. She used to

hang out with the Cool Ones at Daddy-O's Diner. Her skin was as

soft-looking and creamy as the stuff she poured into every cup of

coffee she drank during the late night/early morning get-togethers of

residents of the Who's-Who – musicians, poets, struggling writers

like myself who all lived in this dilapidated building off Wilshire

in Westwood.

Lightbulbs

was also as sweet as the full container of sugar she used in her

sixteen or so cups of coffee. She didn't always engage in the punk

rock counter culture debates of her chain-smoking cronies; mostly,

she sat quietly drawing in her private draft pad. She was an artist.

When I

first met her, back in the Spring of '82, she was already working on

her masterpiece, a series of erotic flower paintings tentatively

titled “Floral Fixation.” I fell in lust with her almost

immediately, like everyone else, and gradually, as I got to know her

better, fell in love with her, like everyone else.

L.A.

1982. Teenage Enema Nurses and Rock Lobsters ruled the airwaves.

Lightbulbs was Neon New Wave before it became Old Ripple. While

living in the Who's Who she ran the rainbow gamut of hair colors,

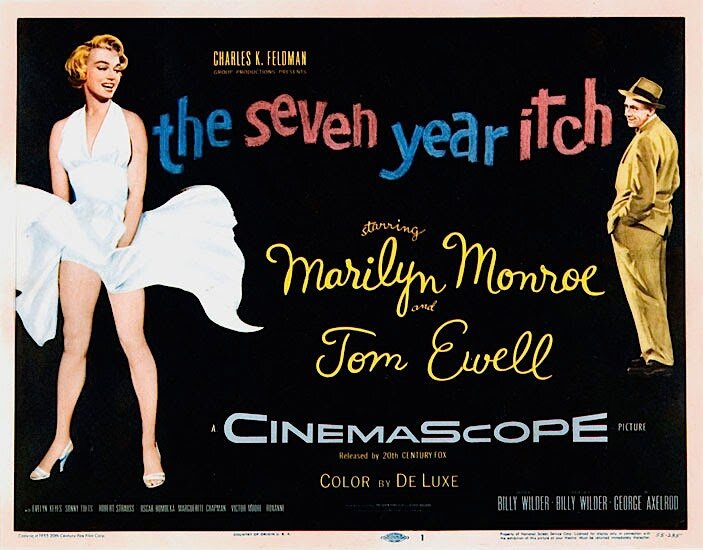

from green to pink to purple to platinum. She finally settled for

blonde after seeing some old photos of Marilyn Monroe in a

memorabilia shop on Hollywood Boulevard. By that time she had already

burned-out on Debbie Harry and Blondie, Roxy Music, David Bowie, all

the New Wave dinosaurs. By the time I met her, in the depth of her

Marilyn phase (she was a sophisticated nineteen, world-weary but

emotionally immature), she was your basic nightclubber, a fan of all

the local bands. My heart broke every time I walked down the hall and

saw some leather-clad, stringy-haired, bleary-eyed punker emerging

from her room the morning after a surreal gig she'd attended. She

loved to dance, she loved to draw, she loved sex. She seemed

unattainable as a lover but all too accessible as a pal, so at the

time I took what I could get.

Clad in a

pink robe, open all the way down, she was kissing Tarantula, a

musician who lived in the Who's Who, when I happened past. Tarantula

and I bumped into each other as he turned to leave. I excused myself

and tried to keep my eyes off of Lightbulbs' creamy cleavage. She

noticed me noticing her though, and, with mock modesty, closed her

robe. Tarantula was obviously stoned and barely acknowledged me. As

he stumbled down the hall back to his own room, Lightbulbs and I

stood awkwardly in her doorway, trying to think of something to say.

“How about some breakfast?” I blurted finally. She said sure, let

me throw something on, which turned out to be a leopard skin halter

top, black matador pants, and pumps, plus her trademark cat-eye

glasses. Lightbulbs was near-sighted, her only physical flaw, as far

as I could tell at the time.

In truth,

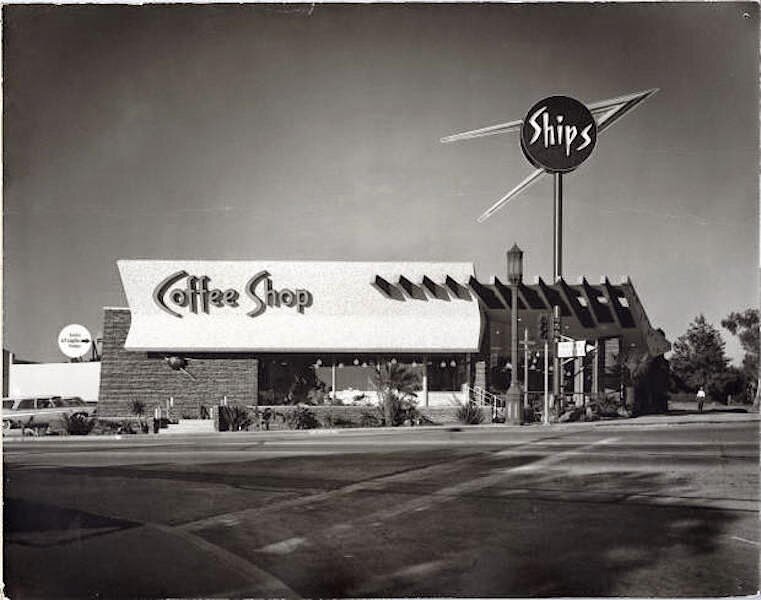

Daddy-O's Diner was really Ship's Coffee Shop, on Wilshire Boulevard,

across from the graveyard where Marilyn Monroe is buried. But

Lightbulbs had dubbed it Daddy-O's Diner since that sounded “more

'50s.” As we walked to Daddy-O's that morning – unusually bright

and crisp and cool for L.A., maybe 65 degrees and mostly overcast –

Lightbulbs had on her Walkman, so I couldn't really talk to her.

When we

got to the coffee shop, I bought a copy of the Times from a box out front

and Lightbulbs stopped the tape. It was a continuous recording of her

favorite song at the moment, “Fade to Grey,” by some Eurotech

group called Visage.

We

snagged one of the smaller booths and ordered right away. “I love

this place,” she said. “Reminds me of a rocket ship, like the one

in Forbidden Planet. You ever see that movie?”

“No,”

I said. I ordered a fried egg sandwich and coffee from Dorothy, our

favorite waitress. She was a legend at the Who's Who, old and feisty

and wisecracking. She's dead now, from an aneurysm. Ship's is gone

now, too. But in my mind, there're still there forever. That whole

time and place was really an era, though none of us knew it at the

time, except when the Who's Who was torn down to make way for an

office building and everyone scattered in different directions, we

all knew it was the end of something special.

But, in

my head, my conversation that complacent morning at Daddy-O's lives

on.

“Guess

who came into work the other day?” she teased me as she put on her

makeup with the aid of a tiny mirror. Lightbulbs was working at the

time in a beauty salon in Century City.

“I give

up. Who?”

“Burt

Ward. Can you believe it? I got his autograph.”

“Who?

Who's that?”

“Robin!

On Batman? Don't you know anything?”

“What

would Robin want in a hair salon?”

“He

wanted to use our bathroom, but it's for customers only, but I let

him use it anyway. And you know who else I saw? In Neiman-Marcus?

Ann-Margret. I was going to go up to her and tell her Viva Las Vegas

used to be my favorite movie when I was a kid, but I figured I'd skip

it. What does she care, right? So what's up with you, Gumshoe? How

come you never talk to me?”

Everyone

called me Gumshoe because I was always reading detective novels. I

used to argue with this other writer at the Who's Who, a poet called

Vomit Comet (he also wrote lyrics for a band in the building), about

whether Raymond Chandler or Charles Bukowski was the great LA bard.

We both compromised and settled on John Fante.

“What

do you mean, how come I never talk to you?” I said. “We're

talking now.”

“Yea,

but never before. Not really. You never go to any clubs, do you?”

“Nah,

I'm not into crowds.”

“Neither

am I.”

“So why

do you go, then? Why hang out with all those types if you're not one

of them?”

“What

types? You mean my friends? Those types you mean?”

“Don't

get mad. Ever hear of Judy Holliday? You remind me of her.”

“Why,

is she a ditz with tits?”

“Um, yeah,

but that's not what I meant. So you like movies a lot, huh?”

Our food

arrived. Lightbulbs had coffee and eggs with ketchup. It looked like

some biological accident, but she scarfed it up with relish.

“What

makes you think I like movies?” she said.

“That's

all you ever talk about.”

“Well,

what else is there? Besides music and sex. Hey, you see Cat People

yet? It's my new favorite. The music's really cool, too. You

should see it, really. Aren't you a writer or something?”

“Yea,

or something.”

"Where are you from?"

"Where are you from?"

“Philly,

Philadelphia.”

“Oh,

yea? No shit. I'm from Kansas.”

“No,

you're not.”

“How

did you know?”

“You

don't fit the farm girl image.”

“Why

not?”

“I

don't know, must be the way you snap your gum.”

“You

should know, Gummy.”

“Please

don't call me Gummy. Gumshoe I can barely take, but Gummy...”

“I'm

from up north. Seattle, then San Francisco. In case you care, that

is.”

“So

where are your folks? Down here?” I asked, leafing through the

Calendar section of the paper.

She

shrugged nonchalantly, lighting a new cigarette. “I lost touch with

them already. My mother's up by Frisco last I heard. My old man might

as well be dead. They're both artists. Anything good playing?”

I was

scanning the movie listings. “A Marilyn Monroe double feature at

the Nuart.”

“Oh,

yea? Let's go, I've never actually seen one of her movies.”

“You

gotta be kiddin'.”

“Why do

you say that?”

“Forget

it. Yea, we can see those tonight.”

“Isn't

the Nuart right across from Dolores' on Santa Monica?”

“Yea,

come to think of it. You like Dolores'?”

“Yea,

it's sorta cool. Kinda dark. You ever been to Zucky's in Santa

Monica?”

“Sure,

whenever I'm down there. I like it.”

“It's

all right. How about Norm's on Pico? Or Ben Frank's on Sunset?”

“What're

you, Miss Coffee Shop of 1982?”

“That's

me, baby. Better believe it.”

Later

that night, after Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How To Marry

a Millionaire, we went to Dolores' and had coffee and mud pie.

“So did

you like those flicks?” I asked her. She was sort of quiet all

evening, I supposed out of awe for her idol. From our breakfast

conversation I discovered we had a few things I common – a fondness

for cloudy days, late night B movies on Channel 5 – but I knew she

had a thing for musicians, of which the Who's Who had an

overabundance. Also, I feared that beneath her hip, liberal exterior

she was just another gold-digger. In a town like this, young, nubile

girls like Lightbulbs had all the angles covered. I was wrong,

though. I was only 22 at the time, and paranoid about being a waiter

in a Venice cafe who scribbled autobiographical sketches by

moonlight. I didn't think a girl like Lightbulbs would want a guy

like me any more than one of those leggy sorority bimbos at UCLA

would. Again, I was wrong, and glad of it.

“Yea,

they were cool,” she said softly. A teardrop fell into her empty

coffee cup.

“Um...are

you okay? Just devastated about Marilyn being dead or...what?”

“I was

thinking about my father.”

“Yea?

How come?”

“I

don't know...let's just drop it.”

“Drop

it? Drop what? What did we pick up?”

“My

father...You remind me of him, a little.”

“Really?

Good.”

“Not

good, really. I hated him.”

“Oh...”

“But

that's not why you remind me of him.” The waitress brought us more

coffee, and shot me a look that accused me of disturbing the young

lady's evening. I let it pass. I put my hand on Lightbulbs' hand, and

her fingers curled around mine. Her hand was warm and moist, and I

grew excited in a very un-platonic way. I wasn't feeling very

fraternal toward her. Or I didn't think I was, by my definition.

“He

raped me,” she sort of whispered into her coffee cup.

“What?”

Which was a stupid thing to say, because I heard her and didn't want

her to have to repeat it, but I was too stunned and inexperienced to

react accordingly. She was really wailing now, and I was torn between

sympathy and morbid fascination, wanting every detail of the

encounter while simultaneously fighting repulsion and an urge to

throw up.

“I

don't want to talk about it,” she said, and I said sure and let it

go. She added one more thing, though, before lapsing into silence:

“Now you know why I am the way I am.”

We didn't

have a date for a long time after that night. She sort of avoided me,

for some reason, like I'd gotten too close and she decided to back

off. I lost a lot of sleep during that period. I was sloppy and lazy

at work and nearly got fired. I wrote something called “Lightbulbs'

Lament,” a sort of prose poem I half-planned to give to her but

tore up at the last minute. I saw more Saturday and Sunday morning

one-night stands leaving her room, and I felt crushed. She always

smiled at me before closing the door.

Finally,

after about a month of being politely ignored, I got up the courage

to knock on her door and ask her out. It was mid-afternoon, but

apparently I'd woken her up. She invited me in anyway. The shades

were pulled down over the window, and the room was a disaster of

dirty laundry and misplaced knickknacks. I saw some guy's underwear

and a used condom and pretended I didn't. Odd art prints adorned the

walls, by people I'd never heard of, but I had a feeling that was

more due to my ignorance than their obscurity. Pop art postcards

lined the walls as well. She slept on a futon with rumpled sheets.

The room was stuffy despite a fan that was on full blast, and smelled

vaguely of sex, perfume, and mildew.

“Ever

been to Junior's?” I asked her, referring to an overpriced Jewish

Deli on Westwood near Pico.

“Um,

sure, once. Why?”

“Wanna

go? My treat?”

“Now?”

“Well...yea.

Why not?”

“It's

still early. I just went to sleep about two hours ago.”

“Sorry

if I woke you. Maybe I should come back later...”

“No!

Don't leave. I'll...throw something on and be right with you.”

She was

entering her Bauhaus/goth period and all her wardrobe was slowly fading to

black, like a lot of the Who's Who. I was getting sick of living

there, to be honest, but it was cheap and even though I had a tough

time sleeping at night with all the noise I knew I'd miss it if I

left. It was just too unique in ways I can't begin to describe. It

was like a cross between Graceland and the House of Dracula, but not

really either in the final analysis.

I could

hear Billy Idol singing “White Wedding” on her Walkman from where

I stood, which was about a foot away as we walked down to Junior's.

She didn't look at me the whole time, but I knew I could corner her

in Junior's.

I ordered

a grilled cheese sandwich with fries and coffee and she ordered

corned beef on rye with coffee.

“I like

it here. It's cozy,” she beamed at me. The caffeine was bringing

her back to me.

“So how

have you been, Gummy?”

I let

that pass. “Peachy. How about you? I missed you, sort of.”

“Why?

We saw each other every day almost ever since...” She sort of

drifted off.

“Since

that night you told me about your old man.”

“I

don't want to talk about it.”

“Well,

I do. At least how it affects us.”

“Us?”

“Us.

Not the United States. You and me. We. Us.”

“Gummy,

don't get the wrong idea. I like you but - “

“As a

friend.”

“Right.”

“So why

are you playing games?'

“What

games?”

“C'mon,

cut the crap, Lightbulbs. Don't get cute.”

She

laughed at my hard-boiled jargon, even though that wasn't really my

intention. I'd just read Mickey Spillane and was feeling tough and

corny. “Lightbulbs?”

“Yea,

that's what people call you behind your back. Didn't you know? I

thought of it, actually.”

“Is

that supposed to be a sexist comment on my tits?”

“Not

really. Well, maybe. Anyway, you're avoiding the issue – ”

“Wanna

go see Blade Runner tonight? It just opened at the Village

Theater, or the one across from it, what's it called – "

“The

Bruin?”

“I

think so. Let's go see it. It sounds cool.”

“I

guess.” I was a little soured on sci-fi at the time, ever since The

Road Warrior came out and all the dudes at the Who's Who began

dressing and acting like Mad Max. Also, the more time I spent with

Lightbulbs, the better the chances of her opening up to me.

She loved

Blade Runner, and wondered why the world – or at least L.A. – couldn't always look the way it did in the film, dark and rainy and

neon-lit. We went to Ship's, I mean Daddy-O's for coffee and cream

pie afterward. Then she got this bright idea.

“Let's

go visit Marilyn!”

We jumped

over the fence to the Westwood Mortuary and found the wall casket

bearing the proper plaque. There were roses in a little vase hanging

next to the grave. They were fresh.

“Probably

from Joe DiMaggio,” Lightbulbs whispered, hushed by reverence.

Impulsively

I took the roses out and gave them to Lightbulbs, kissing her on the

cheek. She started to cry, and I held her. Her wet cheek glistened in

the moonlight.

I walked

her back to the Who's Who and to her door. She led me inside by the

hand and began removing my clothes. I responded naturally, and before

I realized it we were naked and caressing on her futon.

Before I

actually entered her, she whispered in my ear, “I have to be able

to trust you. You're not like the others.” We climaxed at the same

time.

“You

never did tell me why I remind you of your father,” I said later in

the dark. But she had fallen asleep, or pretended to. I lay awake

most of the night.

Word got

out around the Who's Who that Lightbulbs was entertaining the same

guest night after night in her room, and the general mood was on of

shock and outrage. Promiscuity was one of the Who's Who's staples,

along with drunkenness, recklessness, heavy drug use, and overall

decadence and debauchery – all in an aesthetic context, of course.

Everyone was a rebel without a cause, however. Except Lightbulbs and

me. We simply insulated ourselves from the outside world.

In our

coffee shop conversations I avoided anything heavy for fear of

turning her off again. We talked a lot bout art, especially her

ongoing project, “Floral Fixation,” in which orchids looked

suspiciously like female genitalia, and other flowers had penises for

“stems.” I thought it would be a hit exhibit at any local

gallery. Lightbulbs agreed. She was already thinking New York. This

made me nervous. I didn't like the idea of her moving away, but I

didn't tell her. I'd already learned that sometimes distance is

appealing, at least to neurotic women. I was already half in love

with Lightbulbs, but to say she wasn't neurotic would be like saying

she wasn't sexy. Apparently the two go together by nature, at least

in L.A.

I went

shopping with her on Melrose Avenue. I even went with her to the

godforsaken Valley to visit her little friends, fellow would-be

artists with names like Pill-O (yes, she took pills and slept a lot)

and Soap Oprah, who of course was addicted to daytime dramas. I was

with her as summer became fall and then winter, and 1982 faded into

1983. LA gets all its seasons in one day usually, and we both pined

for greener, lusher conditions in which to be poor and in love. As

far as I know she didn't cheat on me, and of course I was faithful to

her, since I'm single-minded by nature. She fell in love with Annie

Lennox of Eurythmics and proclaimed “Sweet Dreams” her new

anthem. We both kept dreaming, oblivious to the future.

1984

found her dressing in purple around the clock, thanks to Prince. I

was a Bruce man myself. Our relationship seemed solid enough for most

of that year. I sold a few stories to some of the smaller magazines,

and she sold a few paintings on Venice Beach. Our relationship was so

stable it was almost boring. But I was happy, and I thought she was,

too.

Many of

her club-going buddies had moved out of the Who's Who into Silverlake

or Hollywood, and she lost touch with most of the party crowd. The

Who's Who was pretty tame by its own standards when the eviction

notices came.

We'd been

living together in my room for most of the previous year by that

time. Now I wondered how this would affect us. Around this time she

met some sleazy art dealer on the beach who owned a small gallery in

Beverly Hills and who was interested in her. Or her work. Both, as it

turned out.

His name

is Simon, but I called him Slimon. Slimon actually wore open shirts

and gold medallions. Subtlety was not his forte. He was around forty,

and owned a Ferrari with a car phone. He was so obvious I couldn't

believe Lightbulbs would even talk shop with him. But he really

wanted “Floral Fixation” to find a proper venue, and in Bev Hills

he could jack up the prices and make a fortune, enough to quit her

current job as a salesgirl in a Westwood boutique. I was working at

an Old World restaurant right near her, hating every miserable moment

of the humiliation that is part of the job description. Being a

waiter was not my forte. My employers figured this out right

before the eviction notices came and they fired me.

It didn't

take a first-class wiseguy to figure out things were rapidly falling

apart.

What else

could go wrong? But as I was knocking on wood, Lightbulbs was getting

knocked up. By either me or Slimon, she didn't know which.

“Why?”

I whispered in our dark room, the night before we had to move out

with no place to go.

“He

reminded me of my father,” she said tearfully. Her show was

scheduled for the next month, and Slimon invited us to stay with him

in his Pacific Palisades home. He had a beautiful guest house, he

said.

“Where

would I sleep?” I asked.

“I'm

sorry,” she sobbed. “I guess it wasn't a good idea. Letting him

fuck me, I mean.”

“How

could you be seduced by a scumbag like that? It's not like you're

hard up. You really are a gold-digger after all.”

She

slapped me and left with a bag of her belongings.

The next

day I took the money the owners of the Who's Who had given all the

evictees to move with and took a train to San Francisco, winding up

in a residential hotel in North Beach.

1985 San

Francisco. Madonna and Miami Vice. Cafe latte and croissants

instead of coffee and grilled cheese sandwiches. Cafes instead of

coffee shops. Unlike L.A., San Fran wasn't trying to imitate the

heartland of America, but European caffe society. It took a while to

get used to, and I missed Lightbulbs so much I couldn't even write.

The weather was nicer here, though, and I knew she'd love the fog.

But I had no way of getting in touch with her. I'd left too

impulsively and was so hurt I never bothered to get a phone number or

address from her or leave one with a mutual friend for her to contact

me. Of course I didn't even know my destination that day, I was so

disoriented. She'd betrayed me. She'd sold out. And I'd take her back

in a New York minute.

Was she

in New York? I lay awake in my little hotel room fantasizing about

Slimon and her and the baby (which I imagined resembled the mutant

infant in David Lynch's Eraserhead) moving to SoHo or

Greenwich Village and living it up. Once “Floral Fixation” caught

on, however, she'd dump Slimon and move on. Maybe then she'd miss me

and find a way to get in touch. Impossible. My hotel room didn't even

have a phone. I was vanishing in Frisco's fog.

After a

series of odd jobs I lucked out with a job at City Lights bookstore.

Someone had died or something and I walked in at just the right

moment. I got into jazz and blues and saw old movies at revival

theaters. Most of the time I was alone. Sometimes I'd make a friend

in Vesuvio next to City Lights and forget my loneliness for a few

hours, but nothing or nobody could replace Lightbulbs in my heart.

She wouldn't go out.

I tried

everything, including playing Phil Collins' “I Don't Care Anymore”

approximately eight hundred times in a row on my portable blaster.

With my earphones on. Didn't work, and I've been a little hard of

hearing ever since.

I

wandered down to the Bay all the time, Fisherman's Wharf and

Ghirardelli Square, usually at twilight when it was at its most

ethereal. I looked at Alcatraz and knew how the inmates must have

felt.

I tried

working on a novel about a prostitute, but sour grapes make for

bitter wine. Lightbulbs was no good as a muse unless I knew she loved

me. Now I wasn't sure anymore. Maybe I'd just been an experiment in

security, emotionally speaking, but when Slimon came along with the

big bucks and hot connections Lightbulbs blew a fuse. She'd been

screwed into a more lucrative socket, and shone brighter than ever.

“Why

should I be selfish?” I asked myself. Slimon had more to offer, and

could afford a family, too. Even Lightbulbs must have had maternal

instincts. Maybe that's why she was attracted to me. But as it turned

out, I was just another moth blinded by her light.

The rest

of the '80s went by in a designer blur. The Micheal Jackson craze

died down, Reagan's term finally ended. The Berlin Wall fell. Am

earthquake upset a World Series between the Giants and the A's. I

barely noticed either.

|

| Original illustration |

Then,

around Christmas of last year, I was walking down Broadway when I

noticed this sign: “XXX LIGHTBULBS LIVE!!!” I couldn't resist. I

walked through the red velvet curtain into the cool, decadent

darkness of the strip joint and got a table near the stage. I'd never

been in one of these dives before – I saw most of the girls without

makeup in my hotel anyway – but I had to make sure that sign was

only a coincidence.

In the

hazy yellow spotlight I saw to my horror it wasn't. Lightbulbs was

not only a topless dancer in this very town, she was something of an

underground celebrity, judging by the catcalls and whistles from the

sailors, bikers, dirtbags, and businessmen around me. At least she

wasn't a yuppie, I told myself with strained reassurance.

It took a

while to get her to notice me, but when the dancers came down off the

stage and began circulating around the tables, I touched Lightbulbs' sweaty loin and made eye contact.

She

gasped, turned around aimlessly, and ran backstage. Some musclebound

jerk with tattoos followed her, and I followed him.

The

memory is messy. Both Lightbulbs and I were in a state of shock, and

everything seemed surreal. The big guy wound up throwing me out, with

her protesting tearfully. I tried to get back in but the bouncer

tossed me back into the alley, barely conscious.

As I sat

in the alley for the next four hours until dawn broke, all I could

think of was how pretty Lightbulbs looked in her natural brown hair.

Around

6am or so, Lightbulbs finally emerged from the side door into the

alley where I was still sitting in a daze.

“How

about some breakfast?” I asked her. She shrugged and said sure, I

know just the place.

We walked

through Chinatown into Union Square and caught a 38 bus on Geary and

took it all the way to the Cliff House. There was a coffee shop on

the cliff called Louis' that afforded a breathtaking view of Seal

Rock and the Pacific. We were both exhausted and still in shock so we

barely spoke on the way there. I sort of rambled on about how I was

doing and what I was doing and so forth. She fell asleep on my

shoulder.

In the

coffee shop we ordered omelets and coffee. She'd given up smoking a

year before, she me to my surprise, though she never was big on

artificial vices anyway, one of her good points. Her greenish-grey

eyes were still pretty, but tired-looking, and not just from lack of

rest. They'd seen a lot during our time apart, but all I could think

of was the moment, of how beautiful the fog was rolling in off the

ocean, engulfing the coffee shop in a misty shroud. It was like a

fantasy come to life. Almost.

“I

missed you,” I said simply.

“You

must think I'm quite a slut,” she said. She'd barely touched her

coffee. “But then I was always a cheap broad, anyway.”

“Don't

talk about yourself like that.”

“Well,

it's so, ain't it? My idea of a fancy time is sitting in a diner at

3am.”

“So?

Mine too, and I'm no punk.”

“I had

an abortion, you know.”

“I

figured you might. What happened to Slimon?”

“Who

cares? After he paid for the abortion, he sort of got bored with me.

I never did have my art show.” She was

trying not to cry, unsuccessfully, and once again our waitress gave

me penetrating looks. “So I just packed up and moved to Palo Alto

and stayed with my mother for a while. Then the men came around

again, but different types. No musicians. Students, jocks, preppies.

Some wanted to marry me, I couldn't believe it. But I thought of you

and what I did to you and figured I didn't deserve any more nice

guys. So I came up here and found a job in that club and started

hanging out with musicians again. I live in this loft in the Mission

with a bunch of dykes. I had a fling with one of them when I decided

to give up on men altogether.”

“Really?”

This news turned me on, and depressed me simultaneously.

“Yea.

It's over now. She moved out. Then...aw, who cares. Who cares,

right?” She finally took a sip of her coffee.

I was

sort of crying now, too. “No matter what, it's good to see you,

Bulbs. Better not cry so much though – you might electrocute

yourself.”

She

smiled wanly and took my hand in hers. “Good to see you too, Gummy.

Or are you Sam Spade now, living in Frisco and all?”

I leaned

over and kissed her. At first she didn't respond, but finally we

wound up necking in our booth and were asked to cut it out or leave.

If we hadn't stopped, we might have wound up making love right there.

Instead we went down by the water and found a private spot behind

some rocks and made love there, with the foamy waves and gulls and

seals drowning out the noise. It was still cold and foggy but we were

warm and cozy and didn't notice.

I fell

asleep for not more than fifteen minutes. When I woke up, she was

gone. For a few panicky minutes I thought maybe she'd drowned

herself, but then I pulled myself together and looked all along the

local coast until nightfall. No Lightbulbs. She'd vanished again.

As I got

back on a 38 bus heading downtown, I noticed a piece of paper had

been stuck inside my jacket pocket. It was a note from Lightbulbs. It

said simply: “I know this is really melodramatic, but I can't stay

with you. I was never raped by my father. I almost wish I had been.

He just ignored me and left me and my mother alone when I was small.

I kept looking for him in other men and never really found him again.

I really did and do care about you Gummy. You came the closest. Maybe

too close. But I feel too cheap now after sleeping around with so

many guys I didn't care about, looking for Daddy. I don't deserve

you. You deserve an angel, not me. Goodbye, and have a nice life.

Love always, Lightbulbs.”

I took

BART into the Mission and just wandered around hoping I'd bump into

her with Fate's help, but I never saw her again.

As I

write this it's 1990, the age of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and rap

music. Turtle crap. Except for the materialism, I miss the '80s, all

the energy and color. I suppose I equate that decade with Lightbulbs,

who for all I know jumped off the Golden Gate bridge. Maybe I'll see

her work one day in a gallery. I can't believe I finally saw her

again after all those years and then lost her forever. Writing this

memoir is also like writing a requiem for an era. Both the past

decade and the girl who made it matter to me exist always at least in

my dreams, just like Marilyn Monroe. Lightbulbs will never dim.

THE

EMANCIPATION OF ANNE FRANK

by Will

Viharo

Originally

published in The Rooster and The Raven, 1991

I loved

her without reason and when I say reason, I mean both senses of the

word. I loved her with no reason, and for no particular reason. I

don't know why, or how. But it doesn't matter. I guess I was just

born with my love for her. All I know for sure is that my love for her could destroy me, but her love for me could save me. I really wish

with all my heart and soul that she is listening to me now. Wherever

you are, Anne...I love you. I always have, and I always will.

It began

a long time ago, when I was about seven or eight. I was living in

Manhattan with my mother, who was absent most of the time, so I spent

much of my time alone. The only exception to my solitude came when my

hired Nanny would drag me outdoors to the Bronx Zoo, which I enjoyed

the first eight or nine times, but after that it became a senseless

obligation, a boring alternative to the sanctity of my indoor

daydreaming. My mother, an actress who starred in many off-Broadway

productions before her third and most debilitating breakdown, always

worried that I would grow up an isolated loner, a prisoner of my own

internal fantasy life. But I never thought of myself as a prisoner,

really. I thought of myself as a clandestine adventurer.

My

favorite sojourns in those days were to the museums off Central Park

– the Natural History and the Met. The dark, ancient ambience of

both of those places made me feel strangely secure, like I was

stepping out of the hectic mainstream of our Armageddon-bound culture

and back into the ageless wombs of History, where no modern harm

could touch me. In my complacent little cocoon of a world there

wasn't any impending fear of global annihilation or Third World

oppression; rather, merely the day-to-day traumas of my mother's

violently alternating moods and my Nanny's cold indifference seemed

horrible enough to warrant escape.

My only

other avenue of freedom stemmed from the television, of which I was

an avid devotee. Countless late-afternoon hours of my youth were

dedicated to the absorption of the animated antics of Speed Racer,

Kimba the White Lion, and Astro Boy, as well as to the “realistic”

escapades of Ernie and Bert and Kermit the Frog. My mother was hardly

ever home except for early in the morning and late at night, so I was

never intercepted in my video addiction. My Nanny considered my

obsession a godsend, and encouraged it relentlessly. As long as I was

left alone, I was in my own private heaven.

The only

time I was really even made aware of my mother's existence came

whenever I overheard her playing music, generally Chopin, Beethoven,

and Gerswhin. But one contemporary song made her personal hit parade

over and over again, until I felt as if the needle of the stereo was

playing in the grooves of my very own mind. The song was “Those

Were the Days.” To this day, that record haunts me, and I haven't

actually heard it – externally – in ages.

I was an

average but earnest student in the private schools I was sent to. I

kept mainly to myself, of course. My best friends in school were

books. I raided the library while my pre-adolescent peers wrestled

around in the playground and watched the older students competing in

the gym. It wasn't that I lacked physical stamina; I was a healthy

kid, attributable to my over-abundance of check-ups, but being alone

so much just never allowed me a chance to cultivate any sustained

interest in sports or the development of machismo. However, I

discovered the beauty, allure, mystery, and elusiveness of the

opposite sex at a very tender age. When I wasn't in the library, I

was falling in love with whatever petite, pretty classmate that

happened to share the same breathing space with me. Because of my

enduring fascination with the company of girls, I was labeled a sissy

by the guys early on, who weren't able to overcome their fears enough

to delve into the same beckoning abyss so soon. I was stealing kisses

while my would-be buddies were still gagging at the mere mention of

Mary Lou or Betty Sue. Their loss, I thought at the time. I was

popular with girls because of the pervasive reluctance at that age to

engage in co-ed activities. The only time I was ever segregated from

my loved ones was when my teacher would snap me back into line. But

that was okay. I usually had a crush on my teachers as well, and

enjoyed the attention.

My first

book completed cover to cover was Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle

Book. After this cherished experience I actually became Mowgli.

Not long after this I read Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Son of

Tarzan, and instantly graduated from the jungles of India to the

wilderness of Africa, and mentally changed my name from Mowgli to

Korak.

In The

Son of Tarzan, Korak finds a beautiful slave girl named Miriam

and rescues her from a libidinous Arab. The two naturally fall in

love and inhabit the savage, emerald domain of the elder Tarzan with

wild abandon and hot-blooded passion. Even before the facts of

sexuality had surfaced in my consciousness, I was suddenly and

vicariously aware of my own body's desires. I envied Korak, and

dreamed of finding my own olive-skinned, loin-clothed slave girl to

rescue and love.

At the

Bronx Zoo with my Nanny, I began projecting myself into the past

lives of my captive companions. Whenever an adult would inquire about

my home life, I politely informed them that I had been raised by wolves in

Central Park. Invariably the response to this declaration was

amusement, a tweak on the cheek or a patronizing pat on the head. But

at the time I not only preferred this fictional background, I

actually began to believe it myself.

After a

dip into Robert Louis Stevenson and a few trips with H.G. Wells, I

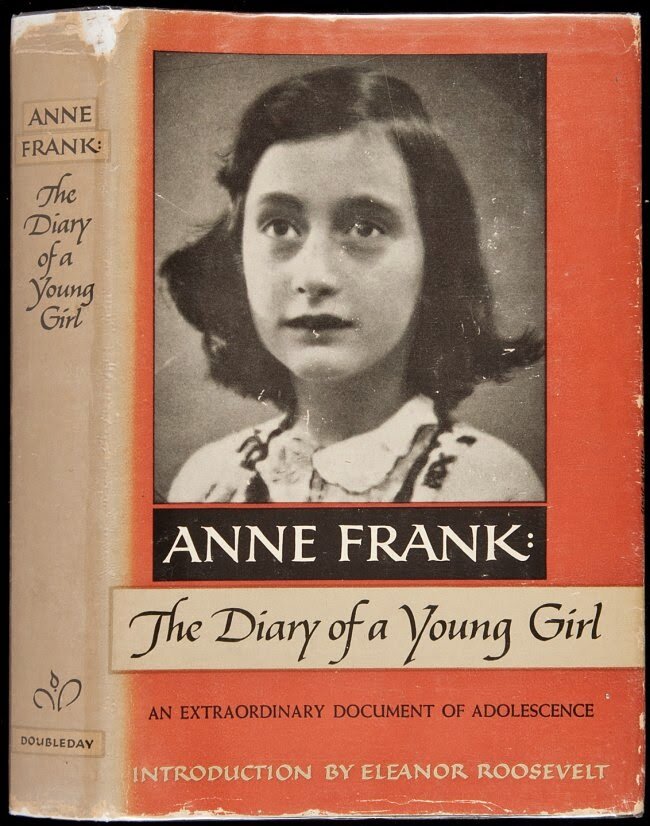

came across The Diary of a Young Girl, by Anne Frank. My

relatively prodigious reading efforts outside of class assignments

had already endeared me to the septuagenarian librarian, and she was

always ready with a heartfelt recommendation whenever I showed my

eager face in the shadowy, musty room. She wasn't sure if I was quite

ready for Anne Frank, I remember, but she told me that it was a book

I should discover one day nonetheless. I had expressed interest in

Gothic horror – specifically Mary Shelley's Frankenstein –

and the librarian strongly urged me to reconsider, citing nightmares

as a common by-product of such escapism. She suggested instead The

Adventures of Tom Sawyer, but in my own precocious fashion I told her

that Twain wasn't my style. I left that day with Lewis Carroll's

Alice books, The Wind in the Willows by

Kenneth Grahame, and Anne Frank's Diary.

It rained

all weekend, fortunately, so my Nanny was not obliged to take me out.

My mother went away for the weekend to the Hamptons to visit some

theater friends, I was told. So my Nanny turned on the television and

disappeared from my sight, sighing with apparent bliss and relief.

Although she had to sleep over instead of going back to Harlem, she

had the place to herself, and I was so easy to watch over it was

criminal. All I heard of my Nanny as I began reading and watching

television was some mumbled chanting, either Far Eastern mysticism or

Haitian voodoo incantations. Whatever, I thought. I was lost inside

myself before long, oblivious to the storm and the sounds of traffic

outside my window.

The two

fairy tale books I found entertaining enough, but decidedly lacking

in substance. At the time the metaphorical dimensions of those books

were lost on me, and I grew bored before completing either of them.

With resolute faith I picked up the Diary and immersed myself

in the mind and heart of the little girl in the Secret Annex.

At first,

I must admit, I had trouble concentrating on the entries, and my

attention kept drifting back to the colorful, violent images on the

tube. But as I got to know Anne better, a deep-rooted empathy was

aroused in me, and I took her plight to heart without fully

understanding the whys and wherefores of her predicament. I was still

very young, and my lessons in history had been reserved for innocuous

patriotism thus far. World War II and the atrocities of the Nazis

were as foreign to me as Europe itself. But still, I could get a

sense of what poor Anne was going through, and in my mind's eye I saw

the Secret Annex where she hid her family as a parallel universe

reflecting my own suffocating circumstances.

I related

all too keenly with Anne's ennui, her bridled playfulness, her

stifled intellect, and her thwarted need for romance. Her interest in

film stars touched me as well, and when my mother finally returned

from her hiatus I begged her for posters and other memorabilia with

which to decorate my room. Hesitantly she complied with my wishes,

but she was consistently opposed to any direct involvement in show

business, not wishing me to follow in her broken footsteps, and never

allowed me to participate in this aspect of her life. I was always

told that when I became a young adult I'd be allowed to see her in a

performance, but by that time I reached maturity her career was

kaput, and not long after she was dead.

So my

Nanny was sent to the local cinema shop to buy me anything I

requested, but only to a point. Randomly I picked out a Marx Brothers

poster and a print of an old movie bill advertising Marilyn Monroe in

The Seven Year Itch. I relished my new “wallpaper” and began to

watch old movies on the weekends to feed my newfound interest.

Insatiably I devoured black and white images of The Bowery Boys,

Jimmy Cagney, and Humphrey Bogart, all the while imagining I was

locked away in the Secret Annex with Anne, watching together our

stolen little TV set, praying the Nazis wouldn't come pounding in any

minute and disrupt our blissful retreat into dreamland.

As I grew

older, I also became more withdrawn. Even in prep school I was known

as the enigmatic loner, though I had friends in each of the pecking

order categories: The Jocks, The Brains, The Nerds, The Hoods, The

Clowns, etc. But I never fit into any of these groups, and while I

sustained my passion for the opposite sex, suddenly, as puberty gave

way to adolescence, I found the agonies of unrequited love.

And yet,

I never felt alone. I excelled in my studies since I had no

extracurricular activities to divert my energies, and I had become an

avid movie buff, spending afternoons within the darkened havens on

Forty Second Street in Times Square. The patrons were often unruly

and interfered with my consummate enjoyment of the proceedings

onscreen, but I never failed to catch the local double feature week

in, week out – premieres as well as revivals. My constant

spiritual companion was Anne, of course. I was going as much for her

as I was for myself.

In my

teens I was exposed to the harsh realities of the vibrant, pulsating

metropolis engulfing me as well as the horrors that had doomed Anne

Frank. I remember seeing Nazis march in Greenwich Village. A riot

ensued that nearly swept me into a paddy wagon, but I escaped

unscathed. In school I poured over volumes detailing the Holocaust,

and my yearning to touch Anne, to hold her and console her, grew more

intense, more real, with each passing year.

I'm

neither German nor Jewish, so Anne's plight did not hit close to home

on any ethnic or political front. Nor was I morally outraged, at

least not more than the next guy, or any conscientious human being.

I was, plain and simply, in love.

My mother

decided to take me to a shrink.

I was

fourteen at the time, a happy victim of wet dreams three times a

night, but other than that a healthy, normal kid (in the locker rooms

at school I noticed all the guys faced their locker, so

obviously I wasn't the only pervert with stained undies). When I told

the doc about my obsession for Anne, he didn't react with quite the

same vehemence as my mother. He didn't consider my love for Anne an

emotional aberration, but a harmless childhood fantasy I would eventually outgrow. For the sake of diplomacy on the homefront I

concurred, even going as far as to quote Freud and Jung in regards to

my case, although of course they were both dead by then and never

even knew I existed. I consoled my mother by watching Masterpiece

Theater religiously and reconciled myself to her good judgement

and worldliness in these matters. I never mentioned Anne to her

again, and quit going to the movies so often. Instead, I began to

keep a journal.

I didn't

model it precisely on Anne's, but I thought of her every night as I

wrote in it, and after a while I even began to write my entires in

the form of letters to her. I was very casual about it, informally

discussing my problems at school and with my mother, who was looking

more and more tired and unhealthy, living on unemployment in between

thankless gigs doing commercials and radio spots. My father was a

television actor on the coast, and I stumbled upon this revelation

quite by accident. He was guest-starring on some cop show as a

gangster, and the resemblance to my reflection in the mirror was

unmistakable. I checked the credits in the end and mentioned the

surname to my mother, since it had been the same as hers long ago,

and in fact was written on my birth certificate. (I'd been given her

stage name when I was too young to protest.) She sat me down and we

had a long talk, after which I cried and wrote about my feelings in

an entry to Anne. I remember feeling genuinely grateful that I had

someone to turn to, even in an epistolary fashion, since my mother

offered little consolation, not wishing to dwell on a subject that

obviously caused her much grief and stress.

She died

about a year after this revelation. I never bothered to get in touch

with my father. I just never felt the need to, and didn't really see

the point.

I missed

my mother when she died though, mourning more for her lost potential

as a thespian than my aborted relationship with her. I poured my

anguish into my journal, commiserating with Anne, who also had a

shaky relationship with her mother.

The quiet

finality of my mother's demise made me realize that Anne was indeed

gone from this world, and was not hiding out in Brazil someplace,

frozen in time and awaiting my arrival in her life. As I approached

eighteen and young manhood, this knowledge dawned on me with

increasing clarity, and the subsequent emptiness gnawed away at me

like maggots on a corpse.

I had

wasted my youth in pursuit of a fantasy, a myth. Anne was dead, and

there was no changing that. Moreover, without my mother to turn to, I

was lost and alone, afraid to depend on the illusion that had

sustained me for so long.

After

graduating from high school, I decided to postpone college and,

without dipping into the trust fund my mother had been saving since I

was an infant, I spent a large portion of my inheritance on a trip to

Europe. A year abroad would set me straight, I reasoned.

At first

I landed in London, and idled away a week there before crossing over

to Paris. I haunted the old stomping grounds of sundry expatriates

writers, searching for a clue to their immortality, but their spirits

were preserved in books, not in the streets of the living. Almost as

soon as I crossed the Atlantic, I was plagued by a disturbing sense

of futility, and a vague melancholia clouded the spectacular vistas

that I had spent my childhood dreaming about.

But there

was one place I had to go before returning to New York and the

confines of familiarity: The Secret Annex in Amsterdam. Of course

that was my destination all along.

It was

March, 1985, the fortieth anniversary of her death in the

concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen. If only she could've remained

hidden for three more months, I could've possibly met her in person,

since Holland had been liberated by the Allies two months before her

death, and one month before her sixteenth birthday, which she never

saw. She would've been Sweet Sixteen, and in love with life (her

exuberance for the imagined world outside of the Annex remained

undiminished right up until the last entry in her Diary, which was

discovered amid the rubble by her father, and privately published).

Her faith in a better world revealed a naïve joy rather than a stoic

tenacity, and it was this unquenchable thirst for truth that so inspired

me and millions of others throughout the world. As I entered the

quaint, cobblestoned Mecca, I felt more in love with her than ever. I

was not in Amsterdam as a tourist, but as a long lost lover seeking

redemption.

If only

she were alive...and yet, it was her untimely, tragic demise at the hands

of traitors and under the auspices of demons that gave her Diary its

everlasting poignancy. She'd always dreamed of being a writer, and

posthumously her ambition was realized far beyond the confines of her

little girl imagination. Her Diary had taken its place in the annals

of Great World Literature. How could she have even hoped that her

little journal, her therapeutic escape, her innocent musings would

amount to a universal classic studied in classrooms for generations?

There

were crowds of people from all over the planet there making the

requisite pilgrimage, but I felt a distinct and special kinship with

the little girl who had once inhabited this tiny attic. I could feel

her spirit move something within me, and I began to cry shamelessly,

oblivious to gawking spectators. I don't know how to describe the

emotions I experienced as I stood within the Secret Annex, so far

from my childhood room in Manhattan, comparatively a palace for a

prince. I guess I felt a mixture of joy and sadness, the tangible

proximity to Anne's lost life pacifying my longing for her, but the

resonant echo of her absence reverberating within my brain and heart.

She was gone, gone forever, years before I had even arrived.

I went

back to New York and lived out my inheritance. I wrote a play, got

rejected, wrote a few more, got rejected, lived in a small, cold room

in the Village, and kept writing. I felt dismally alone and isolated,

without even a fantasy for a foundation. But still, whenever I wrote,

I wrote with Anne in mind, for I wanted to write whatever she

might've written had she lived. I also wrote for my mother, who may

well have been with Anne by then, silently watching over me, waiting

for me to join them.

Dreaming

of abrupt emancipation, I'll forego my sanctuary and carve a niche

for myself in the real world, even if it's like chipping away at

granite with a toothpick. Anne would've wanted that, after all.

MORE SHORT FICTION by Will Viharo

A WRONG TURN AT ALBUQUERQUE (1982) and THE IN-BETWEENERS (1987)

LITTLE BLACK BULLETS (1989) and NIGHT NOTES (1990)

PEOPLE BUG ME (2013)

ESCAPE FROM THRILLVILLE (2014)

SUCKER PUNCH OF THE GODS (Flash Fiction Offensive) (2014)

THE STICK-UP ARTIST (Flash Fiction Offensive) (2015)

THE STICK-UP ARTIST (Flash Fiction Offensive) (2015)

Radio play based on my unpublished novella SHADOW MUSIC (1996)

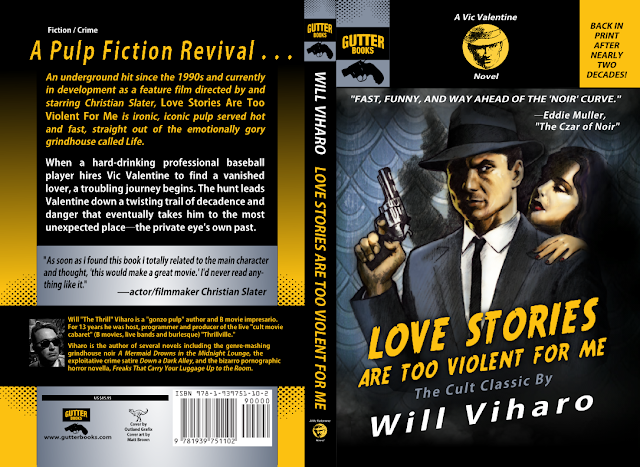

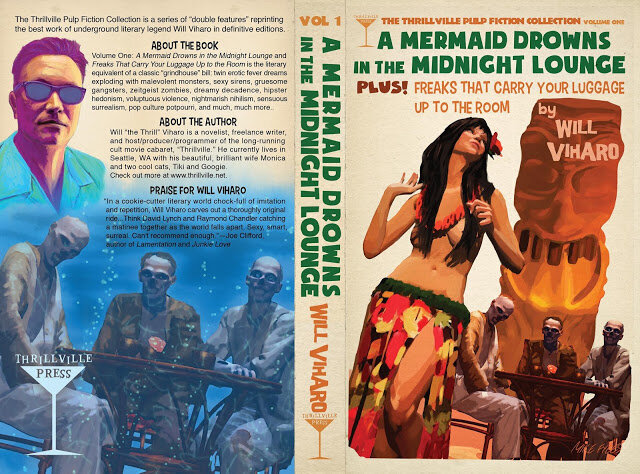

NOW AVAILABLE from THRILLVILLE PRESS:

THE THRILLVILLE PULP FICTION COLLECTION!

| ||||||

| VOLUME ONE: A Mermaid Drowns in the Midnight Lounge and Freaks That Carry Your Luggage Up to the Room BUY

|

| ||||

The new Vic Valentine novel HARD-BOILED HEART now available from Gutter Books! BUY

|

My short story ESCAPE FROM THRILLVILLE as well as my Tribute To Ingrid Bergman

included in this issue of Literary Orphans

|

My short story BEHIND THE BAR is included in this anthology:

|

My Vic Valentine vignette BRAIN MISTRUST is included in this anthology: |

My story SHORT AND CHOPPY and editor Craig T. McNeely's article WILL VIHARO: UNSUNG HERO OF THE PULPS featured in the premiere issue of the new pulp magazine

DARK CORNERS

DARK CORNERS

My story THE LOST SOCK featured in the second issue of DARK CORNERS (Winter 2014)

|

| Screening of the Director's Cut of Jeff M. Giordano's documentary The Thrill Is Gone, Monday, November 17, 2014, 5:30pm at the Alameda Free Library |